Art in the City

Two Artists – two visions of cities

‘The Gerhard Richter Panorama’ at the Tate Modern www.tate.org.uk/modern/ and Grayson Perry’s ‘The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman’ at the British Museum www.britishmuseum.org offered two mind-stretching experiences to start the year.

What is striking in both artists is their extraordinary craftsmanship, the scaffold of their vivid imagination, and their dogged persistence in expressing their reaction to what they see happening in the world, between individuals as well as between whole peoples. Both artists are prolific and constantly experimenting with new media or reinventing tried and tested techniques towards their art. Both combine abstraction with figuration, references to history with contemporary society, introspection and self analysis with denunciation of the world’s failures to grapple with life’s contradictions.

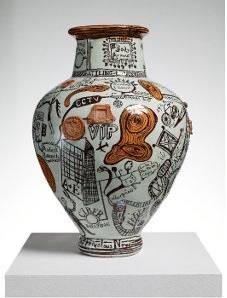

While one is sometimes angry and the other irreverent they both address social dysfunctions, Richter with grey photo-like paintings of the Baader Meinhof gang and Perry by attaching importance to trivia expressed on his “frivolous now” pot; Richter by holding up mirrors to spectators, and Perry by greeting ‘boring cool people’ with their reality TV show taste depicted on the “you are here’’ pot.

Contrast

In many other ways the two artists could not differ more. Richter is German, born in 1932 in Dresden before World War Two which had entered his consciousness at the return of his prisoner of war father; he moved to West Germany when the Berlin wall was erected and where he goes on painting [Godfrey & Serota (eds). Gerhard Richter: A Retrospective 1962-2011. Tate Modern, London, Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Centre Pompidou, Musee national d’art moderne, Paris]. Perry is a generation away, English, born in 1960, missing his father; he was mbraced by the establishment with a Turner Prize in 2003 and elected to the Royal Academy in 2011, the ultimate establishment accolade [Grayson Perry, The Tomb of the Unkown Craftsman, 2011, British Museum].

Richter married three times and fathered children until late, while Perry spent his time between conventional family life, his female side trans-dressed as Claire and his male mantra, represented by Alan Measles the teddy bear from his childhood with whom he was fighting imaginary German armies. Later he travelled there with Measles on his painted motorbike for reconciliation.

While Richter’s show covered his work in West Germany where he had belatedly encountered western surrealism with only minor flashbacks to his pre-capitalist life in the GDR, Perry’s exhibition was a contemporary encounter between ‘my civilisation’ expressed in many new works and entombed objects of civilisations preserved in the British Museum.

Memorable moments

Memorable exhibitions are those which turn spectators into active participants, either by incorporating them into the show or by reaching innermost, often forgotten places. Richter’s mirrors did this physically by making spectators part of his installations. Perry’s provocative pots drew spectators’ minds deeply into their narrative.

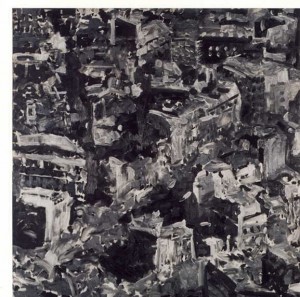

Richter’s ‘damaged landscapes’ – reconstructions of urban destruction – triggered memories, disbelief of so much destruction, critical reconsideration of long buried pasts. Perry’s iron woman and iron man with their respective burdens reminded spectators of their own internalised lest.

Art and self

How to digest the rich tapestry of Richter’s and Perry’s art may be to observe how they relate themselves to their work and how it represents their existential concerns. Richter is revisiting his canvasses time and again, in extreme cases obliterating enormous hyper-realistic landscapes with layers of white paint, the end game of other artists before him. Nevertheless he continues to evoke new horrors and destruction like 9/11.

Perry’ epitome of art is an iron ship sailing into afterlife, laden with numerous artefacts which witness the labour and tears of their creators, but perhaps the stories of his diverse personas gathered in a tapestry format borrowed from other past cultures are more telling.

Such outstanding exhibitions are enriching cities. They are a good reason to come to London and a good reason for Londoners to stay put.